Robert Zemeckis’ Death Becomes Her is an ode to the perils of mortal sin. The 1992 cult classic is far more than just a vehicle for Bruce Willis’ moustache: one could argue that it also performs an incisive takedown of man’s desire to earn the notice of a patriarchal God.

I mean, one could make that argument. Look, reader, I’ll be honest with you: I spend a lot of time fielding the opinions of people who think that genre media and pop culture can’t sustain deep analysis, and I’m feeling very salty about it. People love to corner me at social and professional events to explain why genre fiction just doesn’t merit the kind of thought that real literature deserves. The people who do this seem unaware that a dedicated enough individual could write a thesis on the latent symbolism in a fistful of room-temperature ham salad. So this is my answer to those people: a series of essays focusing on needlessly in-depth literary analysis of a few selected modern classics of genre cinema. You think it’s impossible to find depth of meaning in popular media? Well strap in, kids. We’re riding this little red wagon directly to Hell, and we’re starting with Zemeckis.

Through the character of Dr. Ernest Menville, Zemeckis presents the viewer with a vision of Adam rattling the locked gates of Eden. Menville is introduced to the viewer as a man with a truly winning penchant for the color beige. He has all the personality of a packet of silica gel: bland, unobtrusive, deeply thirsty. He’s simultaneously desperate for affirmation and terrified of being noticed (it’s, like, duality, man…). As suits someone with this specific species of internal conflict, Menville has developed a career in lieu of a personality. He’s a celebrated plastic surgeon, one of the best in a business that thrives on vanity, beauty, and hubristic control over the human form. In his attempts to conquer the limitations of science—a theme that is italicized, underlined, and circled in red pen by the film’s repeated references to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein—Menville seeks to emulate God-as-Creator. He’s a kid wearing his dad’s suit to the dinner table, using oversized vocabulary words in hopes of earning eye contact from a father who will never truly approve of him.

Unfortunately for Ernest Menville, the God of Death Becomes Her went out for cigarettes a few days ago and isn’t checking his pager. Naturally it follows that when actress Madeline Ashton (as portrayed by Meryl Streep) offers Menville an instant of affirmation, he comes running. He abandons his fiancée, Helen Sharp (Goldie Hawn, who does a swell job in Act One of convincing us that her character isn’t as stunning as Goldie Fucking Hawn). The depth of his insecurity makes him a breathtakingly easy mark for Ashton’s predation.

Over the course of this first act of the film, Madeline Ashton and Helen Sharp are established as a Greek Chorus. Their actions direct the viewer’s focus: both characters view Menville with simultaneous desire and disdain. The desire is purely covetous: he is an avatar of triumph. Menville becomes a trophy; caught between the two women, he suffers the fallout of their competition without ever understanding that he’s merely a prize, not a person.

Thus, Ashton’s flirtation is her finishing move, delivered solely to exploit Menville’s weakness—a narrative maneuver which dovetails neatly with the film’s aniconic rebuke of vanity. The text of the film preaches that we mustn’t demean crosses by applying gold leaf to them; by folding like a discount lawn chair at the first sign of attention from a lovely film star, Menville plays out a tidy parable of moral failure. He winds up in a hateful, broken marriage, sexually rejected and intellectually stagnant, finding comfort only in the loving embrace of alcohol. Such, the film posits, are the wages of using betrayal to medicate insecurity.

Who, then, can be surprised at Menville’s reaction to the apparent miracle of his wife’s undeath? When she’s diagnosed as immortal following his inept attempt to murder her, Menville shifts with rapturous precision: from panic, to acceptance, to a deeply misplaced sense of fulfillment. Ernest’s analysis of Ashton’s semi-resurrection is as follows:

“You’re a sign. You’re an omen, a burning bush! […] We’re being told that we belong together. And I’m being called. I’m being challenged. Don’t you see, Madeline? It’s a miracle!”

The entire thesis of Menville’s character is thus delivered, in a scene in which he ignores the trauma his wife has endured. The fact that she was sealed into a body bag and shunted to the morgue is secondary—a signpost only. What Madeline has been through is itself unimportant; what matters is that God the Absentee Father has finally sent Ernest a birthday card. With the volume all the way up, one can just make out Zemeckis’ Hestonian howl in the background of this scene: Vanity! Rank vanity!

For truly, what can be more vain than Menville’s insistence that he’s been singled out as God’s Special Smartest Boy? In this moment, the viewer cannot help but recall the scene in which Madeline accomplishes immortality—a scene that prominently features not a burning bush, but a checkbook. In such a context, Menville’s invocation of a barefoot Moses reads as straw-grasping folly. It’s the kind of pathetic that merits a marrow-deep “yikes.”

These scenes serve as a marvelous framing for Ernest’s moment of truth: the scene in which the jilted Helen Sharp survives a shotgun blast to the midsection (then rises, perforated, to be pissed off about it) is more than just an opportunity for Industrial Light and Magic to twirl their batons. That moment is the Icarian fall from altitude that must follow such a vainglorious pronouncement as “I, Ernest Menville, proud bearer of this truly heinous moustache, have been called by God.” Ernest realizes that his wife’s miraculous semi-resurrection isn’t unique; it’s made suddenly and undeniably clear to him that he isn’t special or worthy. God isn’t coming home for Ernest’s birthday party after all, and he’s forced at last to reckon with his own scorching mediocrity.

The remainder of the film focuses on Ernest’s attempts to escape his ex-fiancée, his wife, and the leader of the immortality cult (as played by a young, mostly-nude Isabella Rossellini, to whom we shall return shortly). He flees as though he is being passionately pursued—a delusion borne of his ardent wish for anyone in the world to find him important. His flight leads him to a climactic confrontation on a rooftop in which he unfurls the full and glorious peacock-tail of his vanity. In this moment, Menville rejects eternal life—and in so doing, the opportunity to survive what appears to be a fatal fall—solely to spite Ashton and Sharp. “You’re on your own,” he announces, as though he is indispensable. Perhaps in that moment, he believes such a thing to be true.

Although this instant of rebellion may seem to transcend the base vanity indicted by the primary plot of the film, the end of the movie delivers a tragic Neitzchean blow to Menville’s journey. He survives his fall, crashing through a stained-glass reproduction of The Creation of Adam in a lovely bit of “this will need to go in the essay” symbolism. The remainder of his days are summarized in the final scene of the film, in which the viewer gets to hear the epilogue of Ernest’s life as narrated by his eulogist.

Ernest, the priest insists in an efficient rejection of Calvinist ethics, attained eternal life through his works on Earth. He founded some charitable causes, and he started a family, and he joined A.A., which is totally something that’s appropriate to disclose to the mourners at someone’s funeral. He had children and grandchildren, and he had a community, and he started hiking, and—the priest asks—isn’t all of that the truest form of immortality?

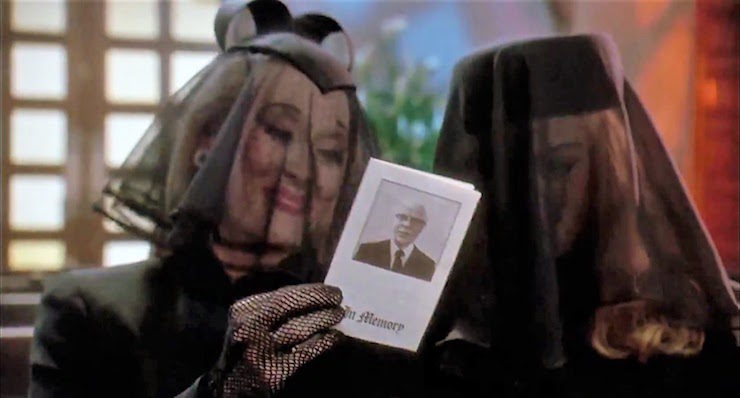

Zemeckis’ framing of this scene answers that question for the viewer. The pews at the funeral are about one-quarter full—a poorer turnout than the nightmarishly bad play that opens the movie. Throughout the scene, the immortal Greek Chorus formed by Helen Sharp and Madeline Ashton heckle the proceedings. The two of them may be corporeally unsound, but at least they’re alive; Ernest Menville is dead. He continued his quest for attention and validation, turning to community and family instead of the two women least likely to ever truly love and respect him. But in the end, regardless of the words of the man in the white collar, Ernest’s life is anything but eternal. Maintain hope or abandon it, Zemeckis posits in this film—it doesn’t matter either way. Ultimately, man’s search for the palpable approval of a patriarchal God is a futile one.

A final (and important) point: as mentioned above, a young Isabella Rossellini plays a supporting role in this film as the serpentine, glamorous, mostly-nude purveyor of an immortality potion. I am led to understand that she used a body double, but it doesn’t really matter if that’s Isabella Rossellini’s real butt or not. She’s awesome. Something something temptation at the foot of the tree of knowledge of good and evil versus temptation at the foot of the tree of life. Seriously, she’s naked for like 90% of her screentime if you don’t count big necklaces, and she’s over-the-top evil for 95% of her screentime, and she’s Isabella Fucking Rossellini for 100% of her screentime.

Regardless of our mortal striving, not one of us is worthy of that.

Hugo, Nebula, and Campbell award finalist Sarah Gailey is an internationally-published writer of fiction and nonfiction. Their work has recently appeared in Mashable, the Boston Globe, and Fireside Fiction. They are a regular contributor for Tor.com and Barnes & Noble. You can find links to their work here. They tweet @gaileyfrey. Their debut novella, River of Teeth, and its sequel Taste of Marrow, are available from Tor.com.

Hugo, Nebula, and Campbell award finalist Sarah Gailey is an internationally-published writer of fiction and nonfiction. Their work has recently appeared in Mashable, the Boston Globe, and Fireside Fiction. They are a regular contributor for Tor.com and Barnes & Noble. You can find links to their work here. They tweet @gaileyfrey. Their debut novella, River of Teeth, and its sequel Taste of Marrow, are available from Tor.com.